Stanleyville feels like the kind of film that will find a small but devoted audience, and it deserves every bit of that devotion. It’s not difficult to find films and television to compare Stanleyville to — it’s like Samuel Beckett by way of Wes Anderson, with Squid Game, Cube, and The Twilight Zone’s “Five Characters in Search of an Exit” all wrapped up in one — yet the film is uniquely its own. Directed by Maxwell McCabe-Lokos, who co-wrote with Rob Benvie, Stanleyville carves its own path in weird cinema with dry humor and mesmerizing surrealism.

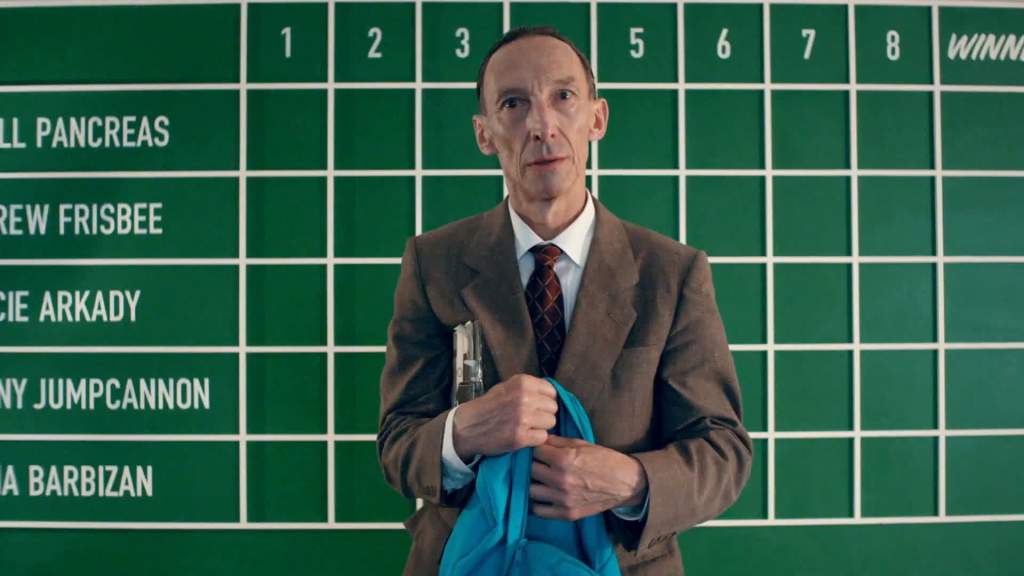

Five people are chosen to participate in a contest. The ostensible prize is an orange SUV, but the true prize is reaching “authentic personal transcendence.” Genre legend Julian Richings (who, coincidentally, also starred in the aforementioned Cube) is Homunculus, a deliriously off-kilter agent of the unnamed organization holding the contest. He tells the contestants to meet at a building at a certain time and then reads them the increasingly bizarre rules of the game. Homunculus occasionally sounds like he is reciting the instructions phonetically, showing little understanding of the proceedings, yet he is also the judge, apparently choosing winners by random in this competition that becomes exceedingly clear as a metaphor for modern life. Richings always does stellar work, and his endearingly bizarre turn as Homunculus is no exception: it’s impossible to take your eyes off him, or to stop thinking about his line readings long after the credits roll.

Insofar as Stanleyville can be said to have a protagonist, Maria Barbizan (Susanne Wuest) is the first contestant we meet, as she walks away from her life with her husband and daughter, dumps all her personal belongings into the garbage, and goes to the mall to sit in a massage chair and ponder her next steps. When Homunculus approaches her and promises her the chance to find her true self, she jumps at the opportunity. Maria is the only contestant who seems interested in the self-actualization part of the contest, and her earnest pursuit of the answers to all her questions in life is Stanleyville’s existential throughline.

When Maria arrives at the mysterious “pavilion” where the contest is to be held, which looks like an abandoned office building, she meets the other contestants. The character names deserve special mention, both because they are delightfully absurd and because they elucidate the film’s tone marvelously. Felicie Arkady (Cara Ricketts) is a woman who will stop at nothing to win that orange SUV. Andrew Frisbee (Christian Serritiello), a finance bro who is very quick to add a “Junior” on the end of his name, wants everyone to know exactly how rich and powerful his father is. Bofill Pancreas (George Tchortov) is a musclehead involved in a protein powder pyramid scheme; Tchortov turns this good-natured doofus into one of the standout characters. Finally, Manny Jumpcannon (Adam Brown) is a narcissistic actor who looks for a loophole in every game in the contest. The whole cast shines — they are all making the same movie, but they also inhabit their own very specific worlds, and the ways that their strange little bubbles bump up against each other make for compelling viewing.

Elliot McCabe-Lokos’s production design also deserves special mention. The “pavilion” is like an avant-garde art exhibit. Seemingly random objects are scattered throughout, lending the film a paradoxical combination of unsettling emptiness and clutter. Again, the metaphors for modern life are clear. The same can be said for the different rounds of the contest. The first three rounds are: “Vital Capacity,” in which the contestants must blow up balloons until they explode (the balloons, that is, not the contestants, though with this film neither one would surprise me); “Cognitive Sequencing,” in which each contestant is given a box of random objects and told to put them in the correct order, even though there is no discernible relationship between any of the objects; and “International Anthem,” in which each contestant must compose and perform a world anthem. This last round is as hilariously weird as you might expect, and the contestants’ entries go a long way in fleshing out their characters. Bofill, for example, raps about Xircolite, the protein powder he consumes and shills in equal measure, while Andrew Frisbee Jr. sings a lilting folk song about his “kill or be killed” capitalist philosophy.

Joseph Shabason’s score sets just as odd a tone as the film’s surrealist dialogue. Manic woodwinds and handclaps keep the viewer’s nerve on edge at strategic points. Sometimes the score features jaunty chamber music, while at other times it can only be described as elevator music in hell. The occasionally frenetic pace of the film also contributes to the nerve-jangling humor, though Stanleyville slows down long enough to give the viewer room to breathe and the actors room to develop their characters. The film’s humor can’t be overstated, though: it is a very dry movie, but it has plenty of rueful laugh-out-loud moments.

Stanleyville is an unflappably weird movie that deserves to find an audience. It is a mannered comedy about the randomness and cruelty of life, with an ending that may polarize viewers but left me an even bigger fan of the film’s particular brand of philosophical questioning. In a cinematic landscape where critics and audiences bemoan the lack of original stories, Stanleyville is a gem that proves that original films are out there waiting to be discovered.